The most difficult procedure in the open boat was rowing. The correspondent and the oiler took turns rowing while the cook bailed water to keep the boat afloat. The correspondent was inexperienced and had to be taught how to row. The men were exhausted and had not slept for two days.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Title | The Open Boat |

| Author | Stephen Crane |

| First Published | 1898 |

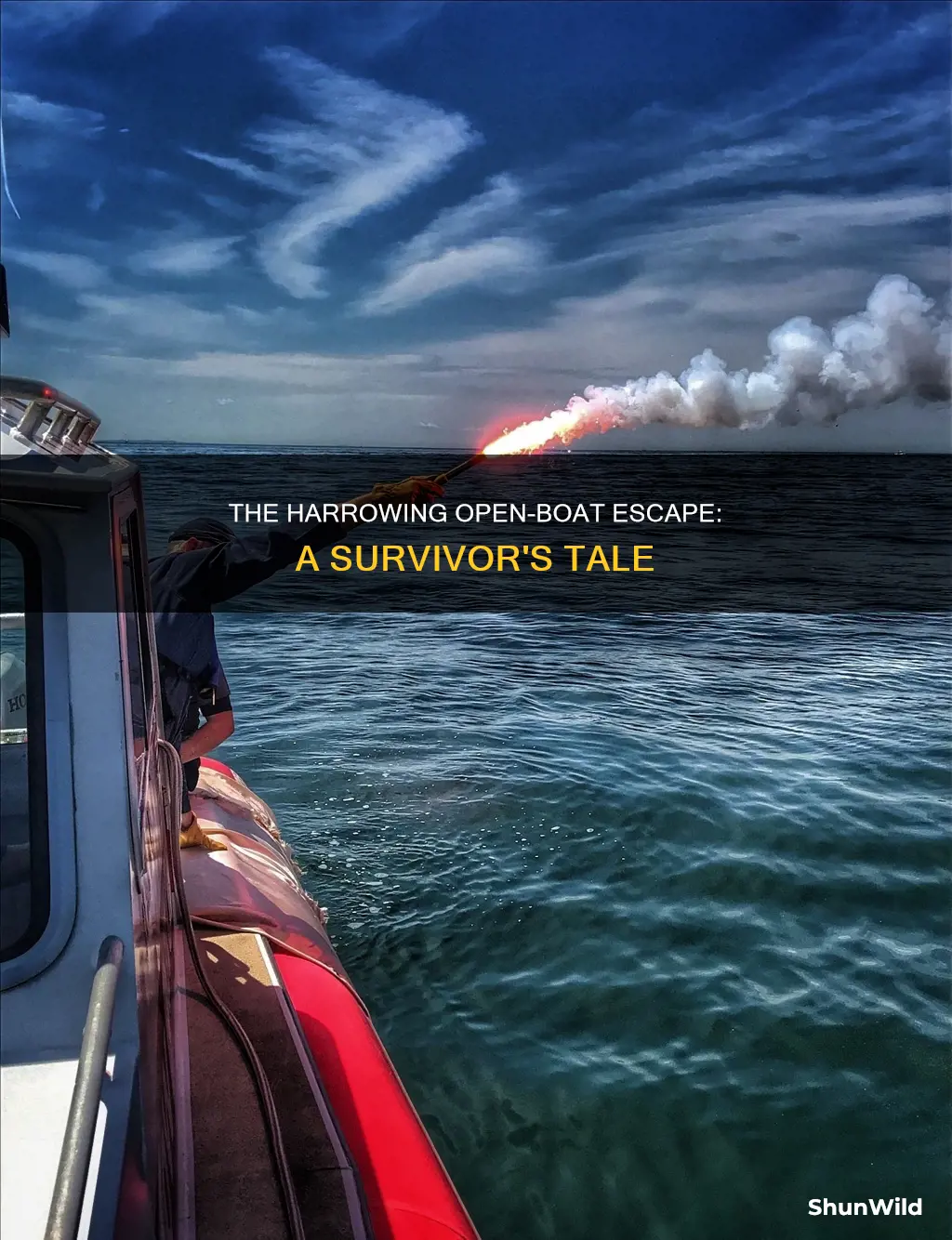

| Based on | Crane's experience of surviving a shipwreck off the coast of Florida |

| Setting | A dinghy in the sea |

| Main Characters | The correspondent, the cook, the captain, the oiler |

| Conflict | Man vs Nature |

What You'll Learn

The correspondent's thoughts on the indifference of nature

The correspondent is a cynical man who has been taught to be cynical of men, but the experience of being stranded in the open boat with the other three men brings him a sense of camaraderie and brotherhood. He feels that the experience is the best of his life.

Boat Launch Service: Getting Your Vessel Water-Ready

You may want to see also

The correspondent's thoughts on the insignificance of his own death

- The correspondent is described as "taught to be cynical of men" and "a man reflecting upon the innumerable flaws of his life".

- The correspondent is "bereft of sympathy" and "cursing softly into the sea" when he is alone in the boat.

- The correspondent is "glad" when he is saved by a man on shore, and he is "grateful" for the "warm and generous" welcome of the land.

Boat Registration Papers: Safe Storage Places

You may want to see also

The correspondent's thoughts on the indifference of nature

> Similar to other Naturalist works, "The Open Boat" scrutinizes the position of man, who has been isolated not only from society, but also from God and nature. The struggle between man and the natural world is the most apparent theme in the work, and while the characters at first believe the turbulent sea to be a hostile force set against them, they come to believe that nature is instead ambivalent. At the beginning of the last section, the correspondent rethinks his view of nature's hostility: "the serenity of nature amid the struggles of the individual—nature in the wind, and nature in the vision of men. She did not seem cruel to him then, nor beneficent, nor treacherous, nor wise. But she was indifferent, flatly indifferent."

>

> The correspondent regularly refers to the sea with feminine pronouns, pitting the four men in the boat against an intangible, yet effeminate, threat; critic Leedice Kissane further pointed to the story's seeming denigration of women, noting the castaways' personification of Fate as "an old ninny-woman" and "an old hen". That nature is ultimately disinterested is an idea that appears in other works by Crane; a poem from Crane's 1899 collection War is Kind and Other Lines also echoes Crane's common theme of universal indifference:

>

> A man said to the universe: "Sir, I exist!" "However," replied the universe, "The fact has not created in me A sense of obligation."

The Complex Web of Ropes on a Sail Boat

You may want to see also

The correspondent's thoughts on the indifference of nature

> The correspondent, as he rowed, looked down at the two men sleeping under-foot. The cook's arm was around the oiler's shoulders, and, with their fragmentary clothing and haggard faces, they were the babes of the sea, a grotesque rendering of the old babes in the wood.

> Later he must have grown stupid at his work, for suddenly there was a growling of water, and a crest came with a roar and a swash into the boat, and it was a wonder that it did not set the cook afloat in his life-belt. The cook continued to sleep, but the oiler sat up, blinking his eyes and shaking with the new cold.

> "Oh, I'm awful sorry, Billie," said the correspondent contritely.

> "That's all right, old boy," said the oiler, and lay down again and was asleep.

> Presently it seemed that even the captain dozed, and the correspondent thought that he was the one man afloat on all the oceans. The wind had a voice as it came over the waves, and it was sadder than the end.

> There was a long, loud swishing astern of the boat, and a gleaming trail of phosphorescence, like blue flame, was furrowed on the black waters. It might have been made by a monstrous knife.

> Then there came a stillness, while the correspondent breathed with the open mouth and looked at the sea.

> Suddenly there was another swish and another long flash of bluish light, and this time it was alongside the boat, and might almost have been reached with an oar. The correspondent saw an enormous fin speed like a shadow through the water, hurling the crystalline spray and leaving the long glowing trail.

> The correspondent looked over his shoulder at the captain. His face was hidden, and he seemed to be asleep. He looked at the babes of the sea. They certainly were asleep. So, being bereft of sympathy, he leaned a little way to one side and swore softly into the sea.

> But the thing did not then leave the vicinity of the boat. Ahead or astern, on one side or the other, at intervals long or short, fled the long sparkling streak, and there was to be heard the whiroo of the dark fin. The speed and power of the thing was greatly to be admired. It cut the water like a gigantic and keen projectile.

> The presence of this biding thing did not affect the man with the same horror that it would if he had been a picnicker. He simply looked at the sea dully and swore in an undertone.

> Nevertheless, it is true that he did not wish to be alone. He wished one of his companions to awaken by chance and keep him company with it. But the captain hung motionless over the water-jar, and the oiler and the cook in the bottom of the boat were plunged in slumber.

> "If I am going to be drowned—if I am going to be drowned—if I am going to be drowned, why, in the name of the seven mad gods who rule the sea, was I allowed to come thus far and contemplate sand and trees?"

> During this dismal night, it may be remarked that a man would conclude that it was really the intention of the seven mad gods to drown him, despite the abominable injustice of it. For it was certainly an abominable injustice to drown a man who had worked so hard, so hard. The man felt it would be a crime most unnatural. Other people had drowned at sea since galleys swarmed with painted sails, but still——

Exploring EPCOT: Boat Ride Essentials

You may want to see also

The correspondent's thoughts on the indifference of nature

> The correspondent regularly refers to the sea with feminine pronouns, pitting the four men in the boat against an intangible, yet effeminate, threat; critic Leedice Kissane further pointed to the story's seeming denigration of women, noting the castaways' personification of Fate as "an old ninny-woman" and "an old hen". That nature is ultimately disinterested is an idea that appears in other works by Crane; a poem from Crane's 1899 collection War is Kind and Other Lines also echoes Crane's common theme of universal indifference:

> A man said to the universe: "Sir, I exist!" "However," replied the universe, "The fact has not created in me A sense of obligation."

The Evolution of Quicksilver Boats: Models and Features

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The most difficult procedure in the open boat was rowing. The correspondent and the oiler took turns rowing, but neither of them were fond of rowing at this time. The correspondent wondered ingenuously how in the name of all that was sane could there be people who thought it amusing to row a boat. It was not an amusement; it was a diabolical punishment, and even a genius of mental aberrations could never conclude that it was anything but a horror to the muscles and a crime against the back.